How the Viking longship came to be

The longship was the culmination of centuries of seafaring innovation that is thought to have started as early as the third century B.C.

In 1880, two young men from Sandefjord, Norway set out on an expedition on the family farm armed with a couple of shovels and an old family legend. They had heard a king had been buried with his ship under a mound on their property, and they wanted to know if the legend was true. Though historians had theorized the existence of the mythical longship, and some picture stones in Sweden depicted them, no one in Norway, or the world for that matter, had ever seen one.

It did not take much digging for the two men to strike proverbial gold. They uncovered the mast of a mysterious ship and soon alerted the authorities. Nicolay Nicolaysen, the then President of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments, caught wind of the find and demanded the amateurs cease digging lest they destroy the ancient artifact. Nicolaysen organized a team to begin an official excavation of the site that started the following month.

What Nicolaysen and his team uncovered confirmed what historians and archeologists had suspected for decades: longships had been real, and not an invention of contemporary chroniclers. The vessel buried underground was a warship measuring 75 feet in length. It had a keelson capable of carrying a mast close to 45 feet in height, which in turn might have supported a sail as large as 800 square feet in breadth. Nicolaysen named it the Gokstad Ship after the farm on which it was found.

The find sparked over 100 years of research on the development and use of the longship in the Viking Age, and more finds along the way have helped to piece together how Viking Age Scandinavians developed the most advanced naval technology of their day. How did the longship come to be? I explore some of the evidence.

The Hjortspring Boat and Early Boat Building (400-300 B.C.)

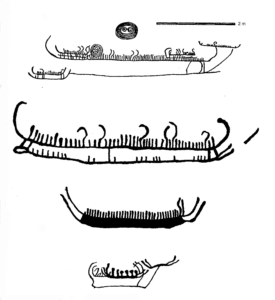

The longship was the culmination of centuries of seafaring innovation that is thought to have started as early as the third century B.C. A chance find on the island of Als, in Denmark, called the Hjortspring Boat (after the bog in which it was found) has helped to inform us on the beginnings of the longship’s evolution. Dating to 400-300 B.C., the Hjortspring Boat was long and thin and resembled the later Scandinavian ships in shape. It does not appear to have ever had a sail, and based on associated petroglyphs, archeologists believe the vessel was propelled by paddles.

The Hjortspring Boat appears to have been a variation on the Celtic shipbuilding tradition attested by the Romans. Given a variety of Celtic artifacts discovered with the vessel and its resemblance to the Celtic skin boats, the theory of Celtic influence in Scandinavian shipbuilding in the early days has some solid evidence. Celtic skin boats were built by constructing ribs off of a central hull and covering them in skins. The Hjortspring Boat has the same ribs but with an original spin: it used overlapped wood planks to form the sides rather than skins. These appear to be an early iteration of the later lapstrake style. The boat also features a pronounced bow and aft, and its length indicates it may have specialized in carrying people, not cargo, across the fjords and islands of Scandinavia.

The Nydam Ship and Roman Influence (300-400 A.D.)

The next step in shipbuilding appears to have occurred as a result of Roman influence. Provincial merchants of Celtic and Germanic origins visited the Scandinavian world in the later Roman period, and their ships may have inspired the next leap in Scandinavian shipbuilding. The Nydam ship, dated to the mid-4th century, shows signs of a variety of shipbuilding techniques similar to the Hjortspring Boat but would have been propelled with oars rather than paddles. While the Nydam ship does not show evidence of having had a sail, many historians think sails may have been developed to a certain extent during this period. The wider consensus, however, places the development of the sail a few decades before the Viking Age alongside the development of the keel.

I argue sails were developed early on, but not by Scandinavians. At the outset of the Migration Period, the Romans who withdrew from the British Isles settled in the Roman province of Armorica, and there they built what historian Jean-Christophe Cassard coined as the First Atlantic Wall. The coast of France was plagued by raids from a seafaring people called the Franks, and they sailed fast ships propelled by sails. If we stick to the stricter definition of the word, these were perhaps the first "Vikings."

The Franks later abandoned their seafaring tradition in favor of continental conquest, but their innovations, which allowed them to sail from the Baltic to the coasts of England and France, would have helped to shape later developments in Scandinavia. Chiefly, I argue, they developed the first sails the Scandinavians would later use to propel their longships, albeit smaller, less effective versions. It also explains how finds similar to the Nydam ship, such as the Sutton Hoo ship in England and the Kvalsund ship in Norway, have been found so far from one another. We should not, however, rule out that determined humans could have rowed that far.

The Keel and the Mast (~700 A.D.)

The innovation of the keel revolutionized shipbuilding in Scandinavia. It appears to have been an original invention, and not one taken from elsewhere. Laying a keel allowed ships to support a larger mast, allowing for a larger sail, and by extension, sailors could harness more wind. Although little of the Kvalsund ship has been found, it is thought to be one of the early iterations of a keeled ship. Unfortunately, not enough of it survived to today, and so most conclusions about it remain dubious at best. Still, it offers us a glimpse into the accelerating pace of innovation in shipbuilding in 8th century Scandinavia.

With a keel rather than a hull as the backbone of the ship, the development of the clinker style, where the hull is made from overlapping strakes (also called lapstrakes), completely replaced the Celtic and Roman building influences. Not long after, the sail took on a whole new form. With more support from a keel, sails grew in size exponentially. Estimates for the sail of the Gokstad ship, a warship found in Norway, put the sail at almost 800 square feet!

Types of Longships and their Uses

The invention of the keel and the mast did not translate solely to warships. Several styles of Viking Age ships have been found over the years, and nowhere have more been found than in the Sjaelland region of Denmark. Beginning in 1962, five ships were discovered near the town

of Skuldelev. These ships are thought to have been sunk in the 11th century to block the bay and prevent warships from attacking the Danish capital of Roskilde. Today, Roskilde is home to the Viking Ship Museum where both originals and reconstructions are on display. The styles include an ocean-going trader, called a Knarr, a coastal trader of the Knarr type, two classic longships, and a small fishing vessel. You can learn more about each at the Viking Ship Museum’s website: https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/visit-the-museum/exhibitions/the-five-viking-ships

More on the Longship

Below you will find two books that are useful in exploring the topic further. You may also find my article on the speed of the longship interesting: Learn more about the speed of longships.